Slavery in the Factory- Part 2

According to Arthur L. Eno, Jr. (Cotton Was King) ”In man’s

four million year career he has revolutionized his economy only twice. The first time was about seven thousand

years ago when man learned to domesticate wild cereal grasses. He went from being a hunter to a farmer…..In

the mid-eighteenth century the second economic revolution introduced factory

production of textile goods on a large scale using machines powered by energy

derived from water-wheels.”

Cotton Was King - A History of Lowell, Massachusetts,

Ed., ArthurL. Eno, Jr.,

New Hampshire Publishing Co.,1976

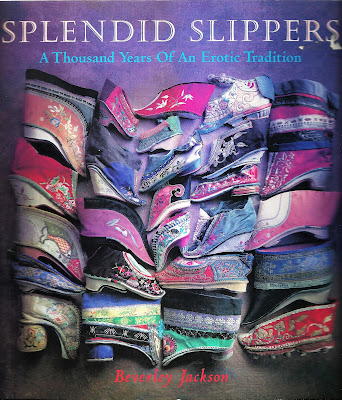

It was the production of textiles that began the industrial

revolution. In the past, textiles for

family use were made in the home. With

the exception of royal workshops which produced a very small quantity of

textiles for the royal entourages, or government controlled guilds producing a

very narrow range of specific textiles, clothing and household linens were made

by family members, often after their work in the fields was completed for the

day. Gradually, small mills began processing

textile fibers, but each mill was specialized, that is, providing only one step

in the process. At this time there were

other mills, of course: grist mills, saw mills, even gunpowder mills. For power, the mills used water, which

fell onto a waterwheel.

Europe was already into their industrial revolution and

sending their exports around the globe when American industrialists began

following their lead by firstly manufacturing the machinery necessary to

produce large quantity of goods.

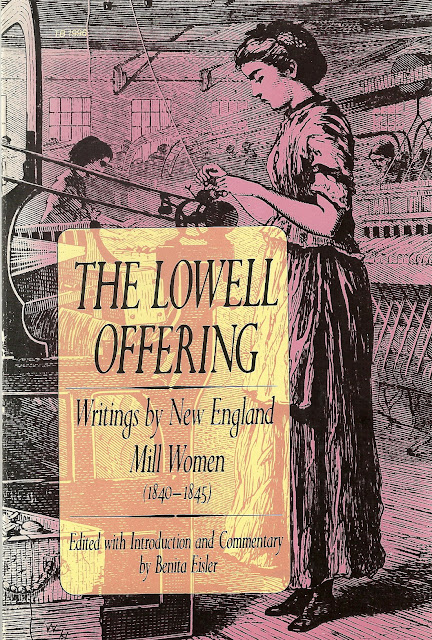

The story of the Lowell Offering is the tale of astute,

resourceful business entrepreneurs seeking high return for their

investments. Francis Cabot Lowell was

an international trader who was much impressed with the European textile

industry. Gathering other investors he

established textile industry in New England and set a precedence for

industrialization throughout the country.

He established a factory system

that produced the entire finished product within one mill. This required large capitalization,

expert management of both resources and

labor, producing cheap goods in quantity.

The Lowell Offering- Writings by New England Mill women (1840-1845), Ed. Benita Eisler, Harper and Row Pub., 1977

Other manufacturers relied on male laborers, some skilled,

some not. The Lowell Experiment hired

young, farm girls from New England. To

assure the families of the safety of their daughters, boarding houses were built

and run by older women, while some girls lived in the city with relatives. The wages for these “mill girls” were paid

in cash, monthly, and they were encouraged to open savings accounts in banks. In other systems, wages were credits at the

“company store” and often the laborers became indebted to the company to the

extent that were not able to leave their employment.

Although the “mill girls” were undoubtedly better off

financially than if they had remained on the farm, there were also

disadvantages. They were required to

remain for at least one year and their lives were strictly regulated, working

long hours. Often the boardinghouses

were overcrowded. The working conditions

in the factory led to health issues: lung disease and typhus.

Cotton Was King, Page 124

|

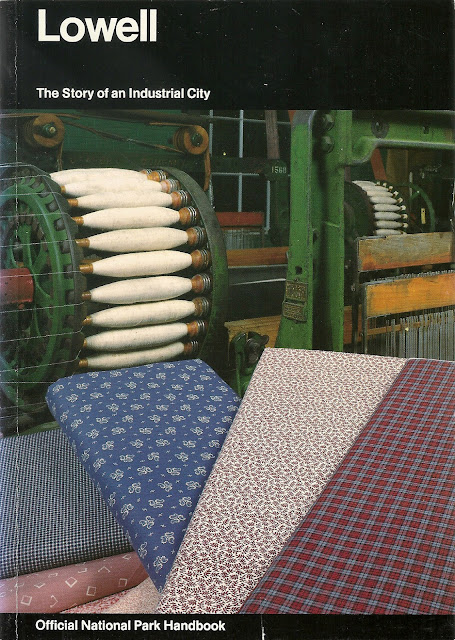

Lowell - The Story of an Industrial City

Produced by the Division of Publications, National Park Service,

U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C., 1992

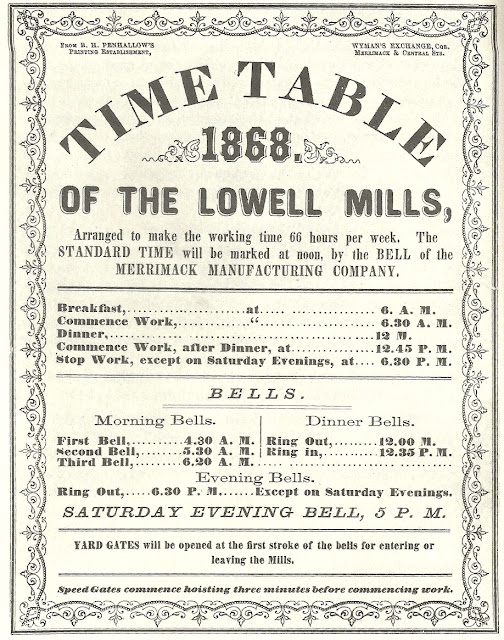

The early years of the 20th century saw production in the Lowell mills falling. Aging machinery was not upgraded. The Yankee “mill girls” were replaced by

immigrant labor. The years following

WW1 saw a decline and hours of production and salaries were reduced. To make the situation worse, there came the

depression.. There was a short reprieve

during the Second World War, but textile manufacturing would go the way of much

manufacturing in the US, elsewhere.